Detachment

why we sing, why we make art, and how we go on living

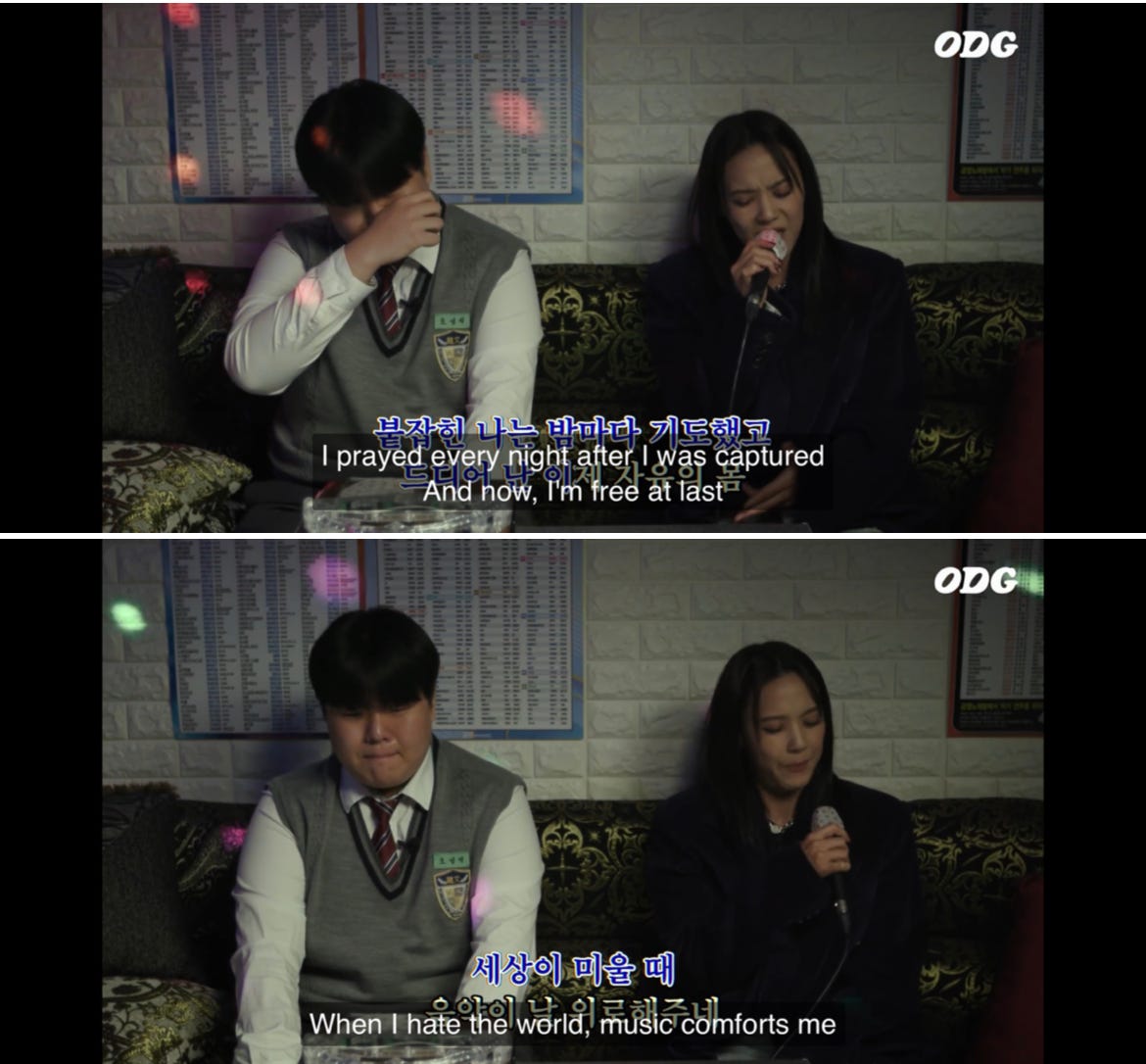

Korean American rapper Yoon Mirae on ODG Noraebang

the kids are alright

A friend recently clued me into ODG Noraebang, a wonderful South Korean music show on YouTube, sponsored by local fashion company ODG, where megastars of the past meet today’s teenagers, most of whom have no clue who they are—and then they open their mouths and sing. It’s surprisingl…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Periphery to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.